Early Black Communities in Southwest Ohio

There were many Black communities in Southwest Ohio in the 1800s. Some are where the Randolph Freedpeople settled after their land in Mercer County was stolen. Others were communities of free Black Americans. Unfortunately, few of these villages survive today. Some became part of larger towns. Most disappeared as their residents moved away.

This blog post is an overview of seven early Black communities in Southwest Ohio.

Carthagena - Mercer County

Carthagena was possibly the largest community of free African Americans in pre-Civil War Ohio. The village, located in Mercer County near Celina, was named for Cartagena, Spain. Charles Moore, a Black man from Kentucky, platted it in 1840. He purchased 160 acres of land in the area.

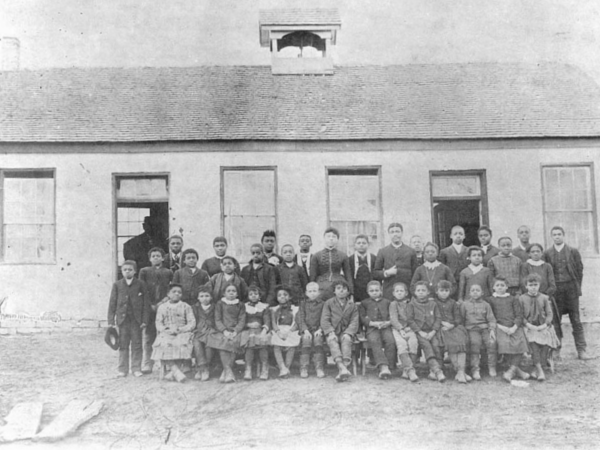

When Moore arrived, there were already Black Americans living in the area. Many of them had traveled from Cincinnati with Augustus Wattles, a Quaker teacher, in 1835. He was interested in establishing schools for Black children. Due to racial tensions, he and fifteen Black families left Cincinnati and headed north. Wattles established the Emlen Institute in 1842. Unfortunately, he closed his school in 1857 due to pressure from white community members.

Black people lived in Carthagena for over 100 years. At one point, over 600 Black and mixed-race families owned more than 10,000 acres of land. The last Black family left Carthagena in the 1960s. The Carthagena Union Cemetery is all that remains of this once vibrant community.

Hanktown - Miami County

Hanktown was one of the towns founded by the Randolph Freedpeople. After they lost their land in Mercer County in 1846, the 383 Freedpeople split into small groups. They joined existing communities or formed their own. Eighty-nine Freedpeople purchased two hundred acres in Union Township, near modern-day Laura. The Wesleyan Methodist Church in western Union Township provided help. Many of the white residents in the area were Quakers. They were also called the Society of Friends and were strong abolitionists.

Hanktown got its name from a local land surveyor named Hanks. It was a farming community, though some worked as day laborers. Twelve Black men from Hanktown served in the Union Army during the Civil War. They were Harrison Gillard, Israel White, Silas White, Spencer White, Hillery White, Julius Young, James Gillard, Corporal Beverly Harris, Nicholas Johnson, Peter Jones, Rev. Joseph Moton, and Benjamin Williams.

Hanktown began to shrink as residents left for job opportunities in larger towns. Very few people lived in the area by 1900. The last known Randolph Freedman living in Hanktown was Ky Jefferson. He lived with several different families in the community, working for his room and board. He passed away in 1931.

All that remains of Hanktown today is the Hanktown Cemetery and a Historical Marker.

Harveysburg - Warren County

Harveysburg was a Quaker community platted by William Harvey and named after him. Many Quakers were against slavery and wanted to help their African American neighbors. The Harvey family established Harveysburg Free Black School in 1831. It was one of the first free schools for Black children in Ohio, but any child could attend.

The Harveysburg school was in operation until the early 1900s. It closed when area schools integrated and became a private home for a while. In 1976 the Harveysburg Bicentennial Committee acquired and restored the building. Today it is the office for the Harveysburg Community Historical Society.

The village of Harveysburg still exists today. It remains a small town, with over 500 residents in the 2010 census. It has been the home of the Ohio Renaissance Festival since its start in 1990.

Marshalltown - Miami County

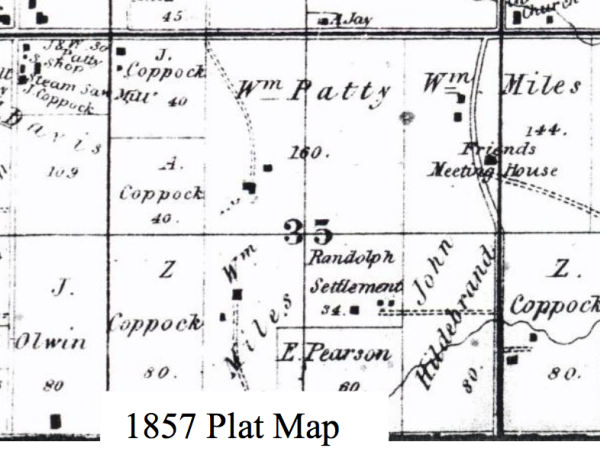

Much like Hanktown, Randolph Freedpeople founded Marshalltown. In October 1847, four of them purchased land from John and Sarah Marshall in Newton Township. Pleasant Hill is near Marshalltown's location. Many in the white community were Quakers and got along well with their new Black neighbors.

Marshalltown existed for about 100 years as a farming community. Today, Marshalltown is an empty field.

Newbern - Shelby County

Newbern, located in Shelby County, was on the Miami and Erie Canal. The first Black mayor of Sidney, James P. Humphrey, was a descendant of the Randolph Freedpeople. He was born in Newbern in 1921. Proud of his ancestors, Humphrey gave many presentations on the Randolph Freedpeople. He also worked to preserve their history.

Rossville - Miami County

Rossville, just northeast of Piqua, began as a white community in 1840. Mr. Knowles laid it out, naming it after Eliza Ross. Ross had built a sawmill and carding mill on the east side of the river. Many Randolph Freedpeople settled in Rossville. They made their homes in the same order they had been in on the plantation in Roanoke, Virginia.

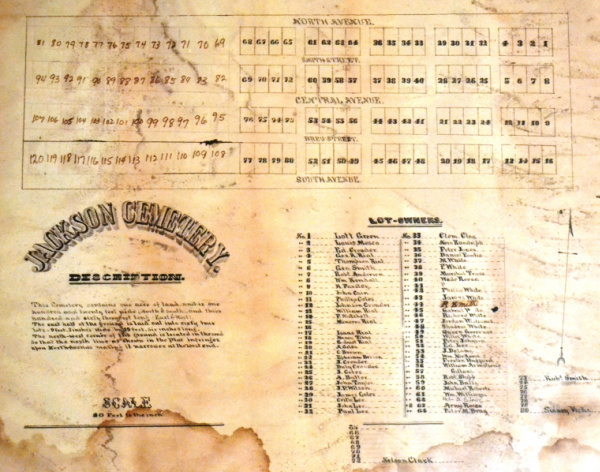

In 1857, William Rial purchased land for the African Jackson Cemetery. He named it for Black attorney Jackson Ross. It became the final resting place for many formerly enslaved people. In total, 134 people were buried in the cemetery, nine of the men served in the Civil War. The community established the African Baptist Church in 1860 and the Rossville school for Black children in 1873.

In 1895, Rossville petitioned to become part of Piqua. The larger city denied their annexation request. York Rial and Joseph Morton started a lawsuit on behalf of all the Randolph Freedpeople. They hoped to recover the land that John Randolph willed to them in Mercer County. The suit became 27 separate cases with 170 heirs. The case went to the Ohio Supreme Court and then the United States Supreme Court. After a ten-year battle, the US Supreme Court ruled that the Mercer County Court of Common Pleas original ruling would stand. That ruling was that Ohio's 21-year statute of limitations prevented the Freedpeople from recovering their land. The injustice of this ruling was devasting for the Freedpeople and their descendants.

By the 1980s, very little of Rossville remained. All of the village may have disappeared if it were not for Helen Gilmore. Gilmore was a descendant of Willian and York Rial. She lived in the York Rial House, which she turned into the Springcreek Rossville Historic House Museum. Gilmore preserved the history of the Randolph Freedpeople and Rossville. She got the York Rial House and the African Jackson Cemetery on the National Register of Historic Places. Through the museum, she preserved family artifacts collected by other Randolph Freedpeople descendants. Gilmore and her husband, Isaac, bequeathed the museum's contents to the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center (NAAMCC). The NAAMCC and the Ohio History Connection used Gilmore's collection to create the exhibit Freed Will: The Randolph Freedpeople From Slavery to Settlement. The traveling show was on display at the Piqua Public Library in November 2018.

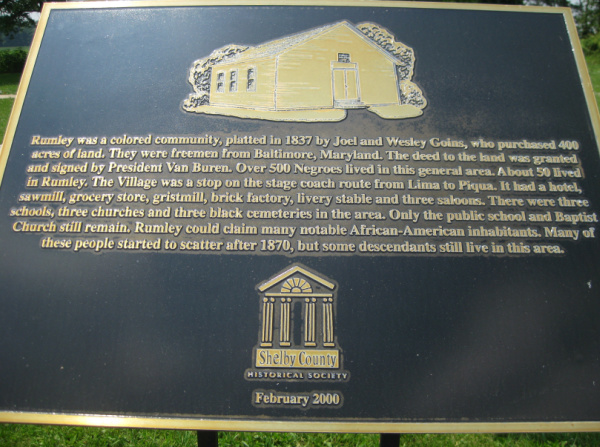

Rumley - Shelby County

Amos Evans mapped Rumley in 1837. A year later, he sold 400 acres of land in Rumley to Joel and Wesley Goings. The brothers were of African and Native American descent and came from the Lett Settlement in Muskingum County, a mixed-race community. The Goings were members of the Wappoo Tribe and Casabo Nation.

The brothers ran several businesses, including a livery stable and a hotel. They also worked as brick masons. Rumley's location on a Native American trail made it a popular stop between Piqua and Lima for those traveling by stagecoach.

The community prospered for nearly 100 years. They had three schools for Black children. They also built three churches, three saloons, and four African American cemeteries. Some of the Randolph Freedpeople settled in Rumley. At one time, African Americans made up nearly half of the population of Rumley. Unfortunately, in the 1930s, the town was abandoned. Many may have left for larger communities due to difficulties in farming.